After the death of Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmet Pasha, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of stagnation, a stagnation felt not only in the political and military spheres but also in the arts. The paucity of known works and artists from this period clearly demonstrates this.

During the reign of Sultan Ahmed III, Louis XIV of France died and was succeeded by his grandson, Louis XV. Ottoman-French relations were fraught with crisis during the reign of Louis XIV. An ambassador was sent to France during that period, but he was not respected there and lived a life of exile. French ambassadors who visited the Ottoman Empire were treated similarly. The decision to send an ambassador was made for reasons such as forgetting the unpleasant events between the two states, the Ottoman Empire sending letters of appreciation and gifts to Louis XV, who had become king as a child, and the assurance that France would stand with him against its enemy, Spain. Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi was appointed head of this delegation. In 1720, Yirmisekiz Mehmed Çelebi and his son, accompanied by nearly forty members of his entourage, sailed to France (Paris). Drawing on his travel notes and experiences, Mehmet Çelebi wrote the book "France Seyahatname," which would have a significant impact on Ottoman social and artistic life. The Ottoman ambassador saw many paintings during his trip and was amazed by how lifelike they appeared. This was because Baroque art effectively employed perspective and the effect of light and shadow, making the works appear more realistic and three-dimensional. Perspective was not a technique frequently used in the Eastern paintings the ambassador had previously seen.

The Ottoman ambassador failed to sign any political or military agreements during this lengthy trip. After a year-long tour of research, the delegation returned with travel notes, memoirs, new ideas, and gifts sent to the sultan by King Louis XV.

As a result of this travel, mutual interaction between the two countries took place. The Western world was introduced to Turkish motifs, and a Turkish fashion began in Paris. Oriental rooms were built in Rococo and Baroque palaces. European nobles wore Turkish clothing and had their portraits painted among carpets and fabrics featuring Turkish motifs. As a result of this interaction, European diplomats, merchants, and travelers visited Ottoman lands throughout the 18th century. Conversely, the Baroque and Rococo styles, which enjoyed their golden age in France, were influential in every field of art. The notes in this travelogue, written under the influence of magnificent works of art in this style, reveal the 15th-century The ornamented gifts sent by Louis, plans for the printing house's arrival in Istanbul, plans for the Sadabat Pavilion, plans for the gardens of the Palace of Versailles, and new works of art with decorations completely unlike those of Turkish art (eyeglasses, binoculars, clocks, large mirrors, small baroque furniture, carpets with various motifs, fabrics, and gobelin rugs) brought European art to the Ottoman palace.

Turkish artists, too, learned and were influenced by Western baroque and rococo art through the observation notes of their trip and the decorations they received as gifts. They gradually began to incorporate them in their works. The rococo style arrived in the Ottoman Empire at roughly the same time as French rococo. While baroque and then rococo art were influential in Europe, rococo art first came to us, and then the baroque style became influential.

Following this trip, ambassadors were sent to other European countries, and reciprocal embassies were established. Conscious movements towards the West began within governmental levels. Subsequently, with the proclamation of the Tanzimat Edict, a decision was made to officially and completely emulate Western influences and to this end, to utilize every aspect of Western expertise. A parallel trend was observed in the arts. Western art influenced various Turkish arts, including architecture, woodworking, plaster, tiles, bookbinding, books, vases, evani, copper ornamentation, papermaking, and fashion. For nearly two centuries, the influence of Rococo art was evident in the ornamentation of manuscripts, architecture, and other artistic disciplines.

This period, which immediately followed the classical period, when the most magnificent and perfect works of Ottoman art were produced, saw the emergence of works with a very different appearance under Western influence. Initially, it was seen as merely European imitation. However, over time, the works proliferated, and eventually, the genre became familiar and popular. Artists of the period combined their own tastes and ancient perspectives with Western influences, creating a new artistic movement known as "Turkish Baroque and Rococo."

The Tulip Era is a period we see as a transition to Westernization and the adoption of Western forms. If we consider the important works of art and artists of this period, the first important aspect is the arrangement of the Sadabad Palace and Kağıthane gardens. A similar setting, modeled after the garden of the Palace of Versailles, is a baroque garden built along the Golden Horn. Fountain pools, open-sided observation pavilions, and columns with dragon-capped heads and water pouring from their mouths were all inspired by the baroque garden layout in Yirmisekiz Mehmet Çelebi's notes.

The floral paintings on the walls of the Fruit Room (Ahmet III's private room) in the harem section of Topkapı Palace, along with the painted flower pots and vases in wall niches, are three-dimensional, naturalistic, and still-life paintings that adorn all the walls and cabinet doors. These dense wall decorations, which also incorporate perspective, are like Ottoman versions of the elaborate ceiling and wall paintings of European baroque and rococo palaces.

The motifs and floral miniatures of painter Ali Üsküdari, the most important illumination, lacquer, miniature, calligraphy, and poet of the Tulip Era, demonstrate the influence of both East and West. The floral miniatures in his book of poems and flower miniatures, "Gazeller," are painted three-dimensionally in a naturalistic style.

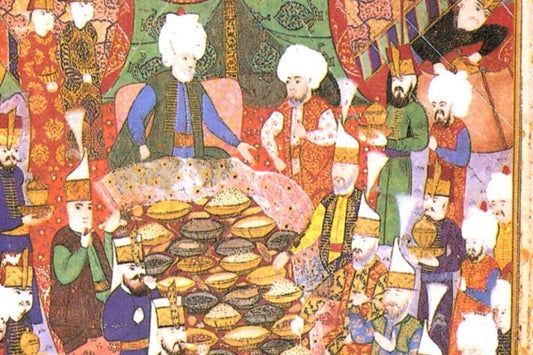

Another important artist of the period was Levni. Levni's "Surname" (Surname) is considered the last example of classical Ottoman illustrated manuscripts. While adhering to traditional Ottoman artistic canons, he also remained open to Western influences. Considered particularly influenced by the works of European painter Jean-Baptiste van Mour, who worked in Istanbul between 1699 and 1737, Levni can be considered one of the last representatives of the classical miniature tradition. His radical innovations in traditional painting, his intensified subjects, and his figures with expressive faces breathed new life into 18th-century Ottoman miniature painting. The painting style of the Tulip Era can be considered the style of Levni, the last great traditionalist and master of manuscript painting.

The long reign of Mahmud I saw the greatest production of works under the influence of European baroque and rococo art. The Nur-u Osmaniye Mosque and Complex was the first baroque mosque built in the Ottoman Empire; it represents a true, local interpretation of the baroque style. Its rich rococo hand-carved ornamentation and baroque architecture, due to its prominent location in a location frequently used by tradesmen and the public, were easily adopted and appreciated. As baroque and rococo ornamentation began to be built in prominent locations such as mosques, tombs, fountains, and public fountains, entrances to covered bazaars, recreational areas, and squares, its spread and adoption became easier. These new motifs, previously used more sparsely, gradually extended to everything from fountain mirrors to door frames, from minaret balconies to grand column capitals, and to all decorated surfaces. Classical moldings with sharp geometric lines were replaced by large concave profiles with the joyful movement of curves, and the ornamentation gradually increased in depth. Thus, the appearance of Istanbul architecture began to change completely ('Baroque and Rococo in Turkish Decorative Arts', Asiye Okumuş, pp. 17-34).