Traditional pottery in Anatolia is divided into two groups based on production quality and the social segment it appeals to: high-quality production centers and folk-style pottery centers.

Pottery is known to have existed in Çatalhöyük and Hacılar, settlements of the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods in Anatolia, dating back to 5000 BC. The Hittite Civilization and Mesopotamia constituted the rich sources of ceramic art in Anatolia. The use of the wheel, which began to be used in the eastern and southeastern regions of Anatolia, first appeared in the Aegean Region with Troy. Around 1200 BC, terracotta artifacts were unearthed in excavations at Smyrna, Klazomenai, Phocaea, and Samos. These include examples with geometric patterns. The Phrygians and Lydians also developed their own unique forms of pottery decoration. It is suggested that the amphora tradition, used for transporting wine and oil, continues today in Menemen pottery.

Various excavations have yielded significant ceramic finds from the Roman and Byzantine periods. The sgraffito, colored glaze applications, and figurative compositions of Byzantine ceramics create a smooth transition between Seljuk and Ottoman ceramics. During the Seljuk period, Persian ceramics influenced Anatolia, and artists were brought from Iran. This influence gradually developed into its own unique style, leaving its mark on Anatolian Seljuk and Ottoman ceramics and ceramic history.

During the 13th-century Seljuk period, works were produced using underglaze, luster, minai, and slip painting techniques. Tiles, glazed bricks, and mosaic bricks are common. Turquoise, eggplant purple, and near-black colors are noteworthy. Examples using these colors often feature sequential, infinity-based decorations. Numerous stylized figural compositions are found in tile examples from the Kubadabad Palace, Kayseri Keykubadiye Palace, Diyarbakır Artuklu Palace, and Konya Alaeddin Palace. When the Seljuks arrived in Anatolia, they brought with them the traditions of Central Asian and Islamic art. Influenced by the Byzantine ceramics existing in Anatolia, they brought a fresh breath of fresh air to ceramic art.

Ceramics from the 14th-century Principalities Period show a simplification compared to the Seljuk Period. İznik and Kütahya emerged as new production centers. İznik focused primarily on palace production, while Kütahya produced works for the public. Turquoise, purple, green, and navy blue dominated the Principalities and Early Ottoman periods.

Blue and white porcelains from the Ming period of China, produced in the 15th century, influenced Ottoman tile art. İznik developed low-grade examples of these porcelains, giving rise to a completely new group of works: blue and white Ottoman ceramics. In the Aegean Region, from the second half of the 14th century to the late 15th century, ceramics with abstract floral patterns in dark blue tones are known as the Miletus type. However, it has been determined that İznik was the center of production for these examples.

İznik was one of the major centers of tile production during the Ottoman period. Tile-making, which began in the early 15th century in İznik, rapidly developed, earning the city the nickname "İznik of Tiled Tiles." Evliya Çelebi, who traveled through İznik in the 17th century, describes in his travelogue how people in nine neighborhoods earned their living by producing tiles and pottery, and that İznik boasted 340 tile kilns. The coral red color that emerged after 1557 gives tiles a distinct beauty. Furthermore, successful tiles were produced in the early 17th century. The Sultan Ahmet Mosque, the Revan and Bağdat Kiosks of Topkapı Palace, and both sides of the Circumcision Chamber gate are adorned with tiles from this period. Over time, architectural activity declined significantly due to financial constraints, and İznik tile-making began to decline. Unable to receive orders, tile workshops gradually began to close down, and in 1716 tile production in Iznik came to an end completely.

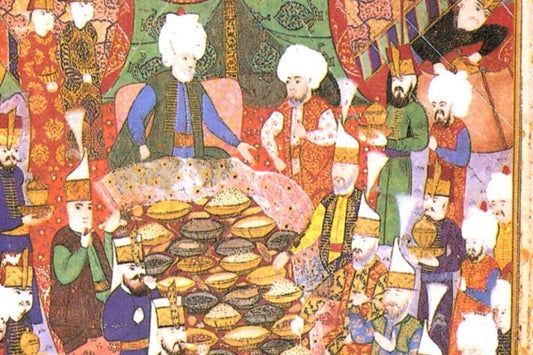

The culmination of the development of tile art in the 16th century must be traced to the Palace Nakkaşhanesi (Palace Nakkaşhanesi). 16th-century tile art appears less as a folk art and more as a state-supported industry. During the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, the "Kaşigeran Division," a division of tile makers, was incorporated into the Ehl-i Hiref, the Ottoman palace artists' organization. After the 17th century, tile art, supported by the palace, declined, and Kütahya, a region focused on folk-style production, came to the fore.

It is known that from the 15th century onward, İznik experienced a technological shift that would ultimately lead to its fame, with the shift from clay-based clay to quartz-based clay (hard, white clay). These ceramics, which acquired a soft porcelain quality, began to replace Chinese porcelain with their often blue-and-white decorations.

In Europe, which hadn't yet adopted porcelain production, Iznik ceramics became valuable imports and wall decorations. Commissioned pieces bearing the coats of arms of established European families are found in various collections, and fragments of these items have been found in the Iznik excavations. Iznik ceramics became fashionable for a time in the Near East, Egypt, the Mediterranean islands, and the West, and were exported in large quantities.

Iznik tilemaking, which experienced its heyday between the 15th and 17th centuries, stagnated at the end of the 17th century with the first applications of the Industrial Revolution in the West and the decline of such state investments, and eventually faded away in the 18th century. It was during this period that Kütahya workshops, which could operate more economically and focused on products required for daily living, emerged.

Ceramic production, which began with the Phrygians in Kütahya and its surrounding area, developed continuously until the end of the Byzantine period. Kütahya remained a transitional zone between the Seljuks and Byzantines for over 100 years. Tile-making during this period incorporated elements of Byzantine and Seljuk art. Later, as Kütahya entered the Beylik Period, Ottoman influence began to be felt.

After switching to white-clay production, the Iznik workshops continued to develop with the support of the palace. Kütahya, on the other hand, served as a secondary center to support Iznik when necessary, and has survived to this day with production geared primarily to public needs.

In the 18th century, during the reign of Ahmet III, Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha brought materials and craftsmen from İznik. He sought to revive tile-making by opening a tile workshop in the Tekfur Palace in Istanbul. These works, notable for their gray and greenish glazes, never achieved the same level of quality.

From the late 17th century to the mid-20th century, Çanakkale emerged as a significant center of ceramic production. Plates, bowls, jars, pitchers, jugs, and vases are frequently used in Çanakkale, and the exact date when ceramics were first produced is unknown. The galleon and sail motifs in these works, created by craftsmen using the region's beige clay, speak to Çanakkale's connection to the sea.

In short, the existence of terracotta materials in the first civilizations established in Anatolia has been revealed through archaeological excavations. Whether it was the Hittite, Ancient Greek, Byzantine, or the Great Seljuk, Anatolian Seljuk, and the subsequent Anatolian Seljuk and Principalities periods, there existed numerous centers where ceramics were used and produced. Chinese wares, arriving via the Silk Road, also entered Anatolia during the Ottoman Empire, resulting in examples of İznik, resembling the Chinese blue and white examples, made using Anatolia's own soil. Later, centers like Kütahya and Çanakkale came to the fore. In the late Ottoman period, products incorporating European motifs entered our ceramic art, beginning with the reign of Abdülhamid, and subsequently increased ('Turkish Ceramic Art in the 20th Century', Gül Erbay Aslıtürk, pp. 65-71).